In a bid to preserve their own industries and reduce their dependency on China, the US and EU recently raised trade barriers against Chinese companies, sparking concerns about the cost and pace of the West’s energy transition. The debate is complex, and environmental and social externalities are a crucial part of it.

In a bid to bolster domestic industries and reduce dependency on Chinese imports, the US and the EU have raised a range of tariff and non-tariff trade barriers against Chinese companies. Recent measures by the US include increasing tariffs on electric vehicles (EVs) from 25% to 100%, those on lithium-ion batteries from 7.5% to 25%, and those on solar cells from 25% to 50%. These actions have sparked concerns about the cost and speed of the energy transition in the West. The reality may be more complex and nuanced than the headlines suggest, with environmental and social externalities a crucial part of the debate.

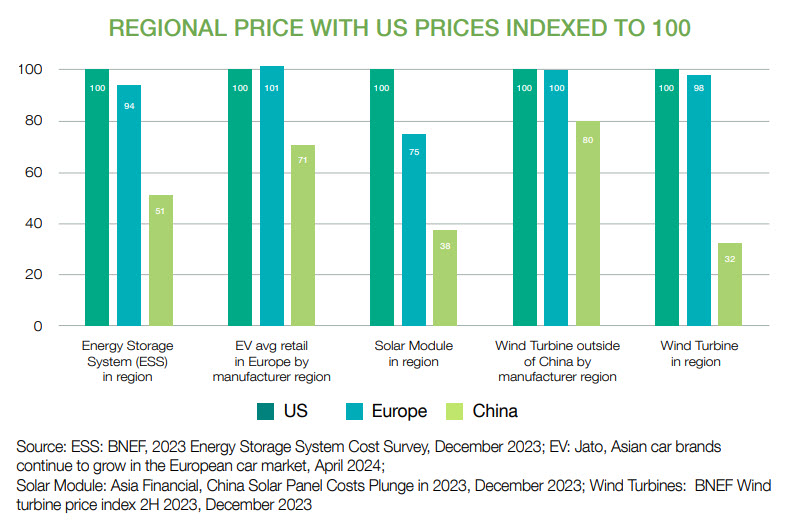

There is no doubt that Chinese companies have played a leading role in reducing the cost of the energy transition through scale-related manufacturing efficiencies and innovation. Chinese companies have significant cost advantages compared with their peers in the West, as can be seen in the chart above which compares the cost levels of some energy transition products by region.

China’s cost advantage is formidable. A European Commission research unit calculated in a report in January that Chinese companies could make solar panels for 16–19 cents per watt of generating capacity. Our own conversations with companies have led us to believe that prices have fallen to as little as 12 cents or less per watt in China. By contrast, it costs European companies 24–30 cents per watt, and American companies about 28 cents. According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, the price differential in wind is around 20% and in energy storage systems (ESS) nearly 50%. In 2023, the average price of a mid-range electric vehicle (EV) produced in China was around USD 25,000, while comparable models from US and European automakers typically cost between USD 35,000 and USD 45,000, representing a price differential of around 60%.

While the overall cost leadership of China is clear, some non-Chinese products are more vulnerable than others; for example, the costs of transition minerals and ESS is likely to increase because of high reliance on China, but other products, like EVs and solar panels, are more competitive.

At the moment, China is a dominant player in all parts of the value chain of energy transition minerals. China has more than a 90% global market share in gallium and refined natural graphite, and more than 80% in refined rare earths and lithium. US dependency on China for these minerals varies by mineral, and for some, such as rare earth elements, it will decline as the US ramps up domestic production. The US is not alone here: the EU has also been actively seeking to diversify its sources of rare earth elements and other critical minerals necessary for renewable energy technologies. However, any mining operation takes time to set up and in the short-to-medium term, the reliance on imports from China means any tariff on these minerals will be an additional cost for consumers. Furthermore, there is a risk that China could prevent the exports of these minerals (there are already some export restrictions), which would escalate this interregional trade war.

In the ESS battery market, Chinese companies are leading in LFP* chemistry which gives advantages like cost, safety and life cycle which cannot currently be matched by South Korean manufacturers. Therefore, in the short term, increased tariffs on Chinese ESS manufacturers will not result in their replacement, it will simply add to the cost burden on the US consumer, which could hurt demand and delay renewables uptake. Furthermore, it conflicts with the US policy of supporting ESS in renewables projects through some of the recent regulatory measures, such as the Inflation Reduction Act, state-level incentives such as those offered in California, and other federal and state grants and funding. There has been a near 50% fall in the cost of battery packs since 2022 which could give developers a margin to absorb some of the tariffs, but this has to be considered alongside an increase in financing costs.

When it comes to solar panels, the US imports very few directly from China. Most panels are imported from Chinese manufacturer facilities in Southeast Asia. Similarly, in EVs, Chinese manufacturers do not have a significant presence in the US. For example, BYD, which became the largest EV maker in the world at the end of 2023, sold 3 million units that year, of which around 240,000 were exported, none to the US. In 2024, BYD plans to double its exports to 500,000 units, but most of this is expected to go to other emerging markets, such as Brazil, Indonesia, and Mexico. Similarly, CATL, the world’s largest manufacturer of lithium-ion batteries, has a direct and indirect exposure to the US of less than 10% of its earnings, most of which is indirect exposure through car exports to the US, such as Tesla’s use of CATL batteries.

One way some Chinese companies are trying to get around trade barriers is a change in their business models towards licence, royalty, and service (LRS). Among the most high-profile examples is CATL which announced just such an arrangement with Ford in 2023 and disclosed that discussions were taking place with other automakers in the US and Europe. They have already announced an agreement with Stellantis in Europe which could potentially use an LRS model.

When looking at the logic behind tariffs, we think it is very important to go beyond cost and note the significant externalities created by a reliance on China. One of the most important of these externalities is the environmental damage of locating much of global manufacturing in a country which has one of the dirtiest electricity grids in the world powered mainly by coal. There are also the additional emissions involved in the transportation of goods over long distances. Other environmental concerns can include pollution and loss of biodiversity created by less stringent regulations and enforcement.

There are also economic and political costs to relying on China; these include a lack of resilience and transparency in the supply chain, controversies around human rights, job losses in the domestic manufacturing industries, and the lack of political will to progress with the energy transition in the absence of visible benefits to local jobs and incomes. This point was recently made in an article by Paul Krugman: “…the political coalition behind the green energy transition shouldn’t be fragile, but it is. If those subsidies are seen as creating jobs in China instead, our last, best hope of avoiding climate catastrophe will be lost – a consideration that easily outweighs all the usual arguments against tariffs.”

Ultimately, the success of transition relies on people believing our interests are aligned with those of the planet – we are all on the same side.

*LFP stands for lithium ferrophosphate and refers to a type of lithium-ion battery that uses lithium iron phosphate as the cathode material. LFP batteries are known for their stability, safety, and longer cycle life compared with other lithium-ion battery chemistries.